04

Guardar os Olhos no Bolso

(Art Critic)

(4 photos / 3166 words)

(Comissioned by Contemporânea)

(2023)

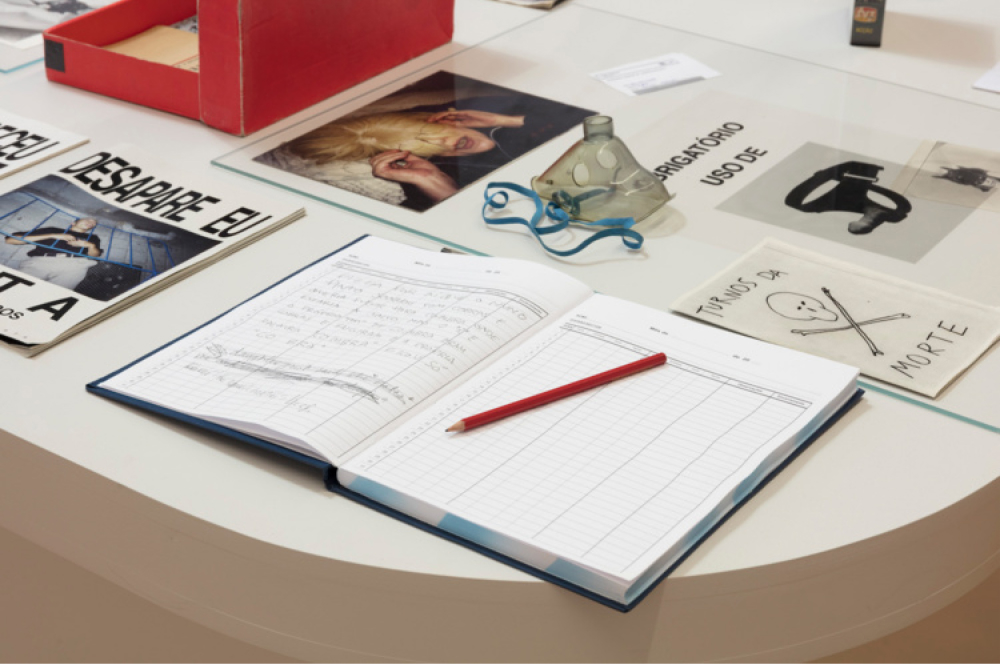

Vistas da exposição no Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar.

Portuguese Version

I

Há uma voz ao longe que, sorrateiramente, se

aconchega ao pé dos ouvidos. Há, pelo ar, uma voz que rodopia e inunda, aos poucos, o espaço

com a sua presença. Há, no movimento serpenteante da voz, um círculo que se

desenha. Há um sussurro discreto, mas persistente, que flutua pelos tímpanos adentro mesmo

que não se queira. Há, em tal voz, uma firmeza e um enigma. As coisas que acontecem no mundo

e há aqui uma marcha em eterno loop.

É

pela discreta onipresença de tal voz, a repetir incessantemente o texto Há, da artista

Cristina Mateus, que a exposição Guardar os Olhos no Bolso se inaugura. Como se

pudesse o pensamento falar em voz alta, as palavras

de teor confessional são reproduzidas em loop a elucubrar sobre as coisas que se

passam na vida. A partir delas, se desenha no espaço um círculo imaginário, ao redor do qual

outras obras de Aida Castro e Maria Mire,

Associação Amigos da Praça dx Anjx, Fernando José Pereira, Francisca Carvalho + Paulo T.

Silva, Horácio Frutuoso, Isabel Baraona, João Fonte Santa, João Pedro Vale e Nuno Alexandre

Ferreira, Missing Artist Foundation, Nuno

Ramalho, PIZZ BUIN, e as trinta e cinco edições do projeto Inland Journal têm um

feliz encontro com parte do acervo de Júlio Pomar.

Do desafio em entrelaçar o projeto

editorial de André Cepeda e Eduardo Matos,

cujo principal ensejo envolve dar aos artistas um espaço para a reflexão sobre suas práticas

(em forma de texto ou de imagem), com o corpo de trabalho de um artista cuja produção é tão

profícua quanto Júlio Pomar, surge uma

exposição que, de certa forma, parece capaz de materializar as ideias em fluxo dentro do

espaço expositivo — ou, ainda, fazer delas seres quase tangíveis. É na primeira sala do

Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar que essa impressão começa

a se revelar: a partir de quatro mesas em formato de L, é instituído um círculo que

centraliza o espaço. Ao redor deste, orbitam instalações sonoras, pinturas, fotografias e

litografias fixadas às paredes. Traçar passos por

esse espaço cria a possibilidade de uma leitura simultaneamente cíclica e autônoma da

exposição.

Com suas curvas vacilantes e seus traços soltos, a série de litografias

Catch, de Júlio Pomar, preenche a parede

ao fundo da sala, deixando os corpos dançantes influenciarem o olhar (ou talvez seja o

pensamento) a desenhar um espaço mental que circunscreve a si mesmo. Quase como se

mimetizasse as ideias a nascerem no cérebro, Guardar os Olhos no Bolso não se trata

propriamente de uma exposição usual de arte contemporânea, na qual a experiência visual

muitas vezes sobrepor-se-ia aos outros sentidos. Há aqui um evidente privilégio pela

cognição, e pela possibilidade de ser

ela o meio para o pensar e o fazer artísticos — ambos entendidos como duas etapas de um

mesmo processo. Em vez do gesto físico, a sinapse. Em vez do fluxo imagético frenético, a

reflexão. Assim, se reproduz também na arquitetura

da exposição a escolha curatorial de Cepeda e Matos em dar ao público a possibilidade de não

se bastar enquanto receptor, mas agir como criador de significados.

Tal caráter emancipatório do espectador em relação à obra de arte não está,

entretanto, presente apenas no pensamento dos curadores. Na última edição do Inland

Journal, lançada a propósito da inauguração da

exposição, está publicada uma parte dos relatórios que Júlio Pomar escreveu durante o tempo

em que foi bolseiro da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, entre 1964 e 1966. Neles, o artista

defende, pelas suas palavras e pelas de Bertolt

Brecht, um pensamento que resguarda o papel do espectador também como produtor de sentido

para a obra de arte. Sob essa mesma perspectiva, se reúne uma panóplia de trabalhos, que

também compartilham de um caráter propositalmente

dúbio, ambíguo e, por vezes, provocador. Em Guardar os Olhos no Bolso, há o convite

a uma experiência antes analítica e crítica do que catártica.

Vistas da exposição no Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar.

II

Tentativa de Reconstrução de Anja Retalhada

para Fundição, 354 Kg e Grandiosa Romaria em Homenagem ao Corpo Ausente da Anja, da

Associação de Amigos da Praça dx Anjx (aapA), encenam um caminho de retomada

simbólica de uma estátua em bronze roubada do espaço público do Porto: A Anja, de

autoria de Mestre José Rodrigues. Uma estátua roubada, irrecuperável, cujo furto propulsiona

a criação do coletivo aapA. Sobre uma das

quatro mesas centrais da exposição, 354 Kg traz uma réplica da cabeça da Anja, feita de

argila policromada em tons de azul, a qual descansa ao lado de Tentativa de Reconstrução

de Anja Retalhada para Fundição, uma

espécie de falsa assemblage, feita sobre impressão fotográfica, que reconstrói o

seu corpo imaginado. Ao lado da mesa, um ecrã reproduz em vídeo a romaria performática feita

pela aapA no parque onde a estátua originalmente

estava. Na parede ao lado, Retrato (duplo) do Artista como Golias, de Júlio Pomar,

sobrevoa essas obras.

Há aqui uma proximidade estética entre a pintura de Pomar, a

colagem e a cabeça da Anja, que se concentra

na fragmentação de suas formas. Entretanto, é ao nível discursivo que a aproximação entre

elas desperta maior interesse. Tanto o retrato de Pomar quanto as obras da aapA parecem

perseguir, em suas representações, justamente

a ausência daquilo que é representado, ou a sua continuação para além do representável. Em

Pomar, a indisciplina do gênero pictórico ou a natureza de sua própria relação com aquele

que o pintor representa. Nas obras da aapA,

o significado da irremediável perda da estátua na realidade concreta da cidade, ou a arte

enquanto manifestação do poder de agência dos indivíduos em sociedade. Em ambos, há o

reconhecimento de que a obra de arte não termina

em si mesma.

É também nessa espécie de vácuo cognoscível que habita parte das obras

que ocupam o segundo piso da exposição. Logo na passagem entre a primeira sala e o andar de

cima, No Campo Artístico, de Nuno

Ramalho, dispõe de dois elementos: uma folha de papel milimetrado em vermelho, com alguns de

seus pequenos quadrados preenchidos na mesma cor das margens, resguardada por um vidro, ao

pé das escadas; e um movimento acústico

criado a partir de duas colunas sonoras, uma instalada no degrau do meio e outra no último.

As escadas são, assim, preenchidas por vozes infantis, robóticas e caricaturais,

interpeladas por ruídos e gritos, que discutem entre

si posições filosóficas sobre a arte. Embora haja ritmo, pausas e frases com nexo na

conversa, a ambiência sonora que se cria ameaça se tornar cacofônica a todo o tempo — o que

se dá, principalmente, pela estranheza das vozes

e pela falta de linearidade no tom dos discursos. Provocante e propositalmente confusa, a

obra crava uma afiada agulha na epiderme de um mundo artístico tão hermeticamente fechado em

si mesmo que já quase se afundou no lago-espelho.

No entanto, não deixa de ser curioso que tal mundo se mostre estranhamente propício a

presentear liberdade ao pensamento.

Partilhando de tal bem-humorada acidez, YOLO

#1, #2, #3, do coletivo PIZZ BUIN, se encontra

à entrada do segundo piso da exposição. Trata-se de três televisores de tubo empilhados,

cada um a reproduzir um trecho de aproximadamente vinte minutos de um scroll feito em uma

conversa entre as artistas do coletivo em um

grupo do Whatsapp. Outra vez, é a arte a falar sobre si mesma nessa versão

contemporânea da torre de Babel. Entre memes e apontamentos sobre a filosofia estética, são

discutidas as problemáticas referentes ao meio

das artes — desde a posição ocupada pelo espectador em relação à obra de arte, até o

funcionamento dos sistemas de financiamento e as suas implicações práticas na vida

financeira dos artistas. É preciso certo distanciamento

para não deixar o pensamento se enganar e perceber a conversa como um testemunho da dinâmica

cotidiana das PIZZ BUIN. Isto é, ainda que a mesma existisse antes da intenção de a

transformar em uma peça expositiva, é a obra de

arte aquilo que o público tem diante de si. Nela, as artistas se colocam, simultaneamente,

como objetos da especulação do público e sujeitos na produção da obra.

Em certa

medida, a continuação do percurso pelo segundo

piso da exposição parece funcionar como um boomerang. Ao fundo da sala, quando

talvez a exposição acabasse, repousa sobre a última mesa do espaço a versão original dos

relatórios de Júlio Pomar que foram publicados

na trigésima quinta edição do Inland Journal. Nas palavras ali contidas, uma leitura mais

dedicada é capaz de vislumbrar um convite implícito para retornar ao início da exposição —

cumprindo, assim, o circulo imaginário percebido

ao início. Porém agora, a partir do pensamento de Pomar, à procura de uma nova

leitura de tudo que ali se encontra, e atenta às potências contidas na relação

entre obra de arte e espectador.

Ao fim, é possível

perceber que Guardar os Olhos no Bolso sobrevive em parte de uma vocação da arte,

presente principalmente a partir de sua história moderna, para pousar o pensamento sobre si

mesma. É esse recurso, uma espécie de metalinguagem,

que permeia os estratos que originam os trabalhos que compõem a exposição. Diante do

espelho, são desveladas as camadas que sustentam os sistemas de poder que mantém o campo

artístico em movimento (a crítica, os espaços institucionais,

os apoios econômicos às artes, quem tem acesso a eles, o conceito de autoria, o papel do

público dentro dessa estrutura, ad aeternum no vórtice de suas inerentes

problemáticas). E é no trilhar desse caminho que se

desnuda o ponto de encontro entre a empreitada do Inland Journal e o legado de

Júlio Pomar.

Exhibition view at Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar.

English Version

I

There is a distant voice that stealthily nestles

by the ear. Through the air, there is a voice that twirls and gradually floods the room with

its presence. Within the serpentine movement of the voice, a circle is

drawn. There is a discreet yet persistent whisper that floats into the eardrums, uninvited

yet unwavering. In such a voice, there is a firmness and an enigma. There is this voice that

marches in an eternal loop.

It is

through the discreet omnipresence of this voice, ceaselessly repeating the words from the

text Há (There is), by the artist Cristina Mateus, that the exhibition Guardar

os Olhos no Bolso is inaugurated. As

if thoughts could speak aloud, her confessional words are reproduced in a loop, ruminating

on the events that unfold in life. From these cyclical words, an imaginary circle is traced

in space — around which a collection of

works by Aida Castro and Maria Mire, Associação Amigos da Praça dx Anjx, Fernando José

Pereira, Francisca Carvalho + Paulo T. Silva, Horácio Frutuoso, Isabel Baraona, João Fonte

Santa, João Pedro Vale and Nuno Alexandre Ferreira,

Missing Artist Foundation, Nuno Ramalho, PIZZ BUIN, and the thirty-five editions of the

Inland Journal project have a joyful encounter with part of Júlio Pomar's

collection.

From the challenge of intertwining

this editorial project by André Cepeda and Eduardo Matos — which intends to provide artists

with a space for reflection on their practices through text or image — with the body of work

of an artist as prolific as Júlio Pomar,

an exhibition emerges and, in a sense, seems capable of materializing ideas in flux — or

even turning them into almost tangible beings. It is in the first room of the Júlio Pomar

Atelier-Museum that this impression begins to

reveal itself: four L-shaped tables establish a circle that centralizes the space. Around

them, floats a small collection of sound installations, paintings, photographs, and

lithographs fixed to the walls. Navigating through

this space creates the possibility of a simultaneously cyclical and autonomous reading of

the exhibition.

With its wavering curves and loose strokes, Júlio Pomar's

Catch lithograph series fills the wall at the

back of the room, allowing its dancing bodies to influence the gaze (or perhaps the thought)

to draw a mental space that circumscribes itself. Almost as if mimicking the ideas being

born inside the brain, Guardar os Olhos no Bolso is not a conventional contemporary

art exhibition, in which visual experience often overshadows the other senses. There is a

clear emphasis on the cognitive system here, and on the possibility of it being the means

for artistic

thinking and creation — both understood as two stages of a same process. Instead of physical

gestures, there are synapses. Instead of frenetic imagery flow, there is reflection. Thus,

the curatorial choice of Cepeda and Matos

to give the public the possibility of not being satisfied merely as recipients but to act as

creators of meaning is also reproduced in the architecture of the

exhibition.

However, this emancipatory nature of the spectator

in relation to the artwork is not solely present in the curators' thinking. In the latest

edition of Inland Journal, released to coincide with the exhibition's inauguration,

parts of the reports written by Júlio Pomar

during the time he was granted a scholarship from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation,

between 1964 and 1966, is published. In these reports, the artist defends, through his own

words and those of Bertolt Brecht, a point of

view that upholds the role of the viewer as a producer of meaning for the artwork. Parting

from this same perspective, a plethora of works is brought together, sharing intentionally

ambiguous, provocative, and at times dualistic

characteristics. In Guardar os Olhos no Bolso, there is an invitation to an

experience that is more analytical and critical rather than cathartic.

Exhibition view at Atelier-Museu Júlio Pomar.