03

Perfil: Musa Paradisiaca

(Art Critic)

(4 photos / 2487 words)

(Comissioned by Contemporânea)

(2023)

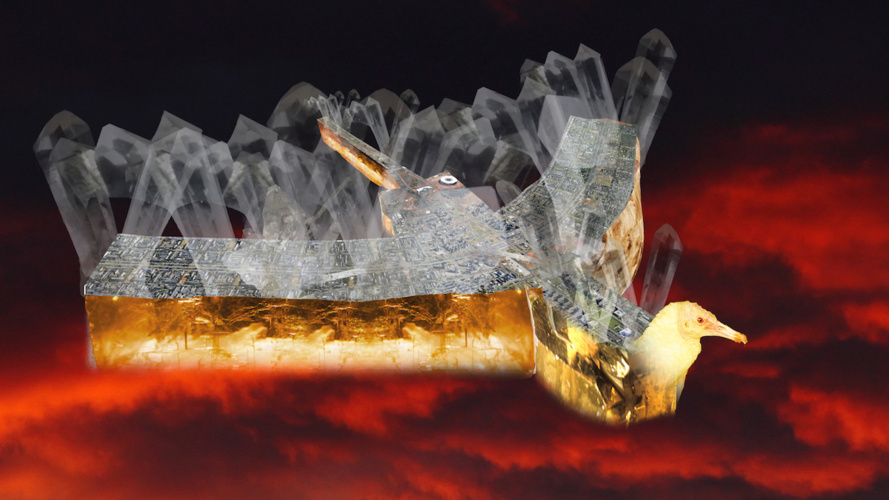

Vistas da intervenção "Solar Boat" na BoCA Bienal, 2021.

Portuguese Version

I

Desde um Sol artificial, uma fonte de luz e

calor concentrados, o tempo dentro da sala escura é marcado por um cíclico apagar e

reacender — uma simulação da natureza intermitente do curso de um dia. Ao redor, qualquer

materialidade se dissipa, abandonando o corpo em um negro vácuo e, assim, tornando esse Sol

a única referência espacial possível. Como se presenciássemos um momento para além do

futuro, no qual poucos resquícios de humanidade

persistiram, tal Sol se transmuta em uma estrutura metálica de presença opressora e divide a

origem de sua luz, antes única, em pequenas esferas, como réplicas de si mesma. No fundo

oposto da sala onde o novo Sol ostensivamente

se faz presente, três objetos feitos para a escuta e reprodução sonoras possibilitam a

perturbação do sepulcral silêncio. Pela primeira vez desde que adentramos o espaço, alguma

presença familiar é reconhecível: um adulto e

uma criança engajam em uma conversa sem perceptível linearidade ou nexo, mas que,

entretanto, possui um evidente caráter dialógico. Imersos no soturno vazio desse espaço

espetacularmente construído, perdemos a capacidade de

distinguir o início do fim, o surgimento do desaparecimento da linguagem, o passado do

presente e o presente do futuro.

A ambiguidade desse estado não é fruto do acaso, mas

característica desenvolvida ao longo de todo

um percurso e fulcral ao ímpeto criador da dupla que tem assinado trabalhos sob a insígnia

de Musa Paradisiaca desde 2010. Em Solar, exposição inaugurada no último mês de

Maio na Appleton [Box], ela é, entretanto,

levada a certo extremo. Talvez seja essa uma consequência de processos que, costumeiramente,

envolvem a participação ativa de muitas pessoas que colaboram com a dupla composta por

Eduardo Guerra e Miguel Ferrão. Especificamente

nessa exposição, a curadora Claudia Pestana foi uma peça fundamental ao puzzle

criativo responsável pela reapropriação de Solar Boat — uma experiência limítrofe entre

performance e happening realizada no âmbito

da bienal BoCA, em 2021, na qual a mesma instalação sonora foi apresentada ao longo de uma

viagem em um barco movido à energia solar por uma lagoa em Ria Formosa, em Faro,

Algarve.

No percurso de deslocamento físico

e conceitual da obra, desde a ampla e idílica paisagem algarvia até o white cube da

galeria, a representação da presença solar — assim como o próprio entendimento dessa palavra

— se transmutou do abstracionismo à materialidade;

ao passo que a espacialidade seguiu a contramão, se desprendendo por completo de qualquer

referencial figurativo ou material e encontrando no negro vácuo uma nova maneira de existir.

Em Solar, as únicas imagens que

se revelam são aquelas que o pensamento, em conversa com a instalação sonora, forja no

imaginário — tendo elas lastro em uma percepção dialógica da obra ou não. Tal interação que

assim se cria configura uma hipótese, intrinsicamente

relacionada à prática da Musa Paradisiaca: a de uma protolinguagem nascida nos interstícios

dos sentidos, das palavras, das imagens e de tudo aquilo que configura o

sensível.

Esse exercício, ao qual poderíamos referenciar

enquanto uma espécie de abstração, reavaliação ou, ainda, desarticulação da linguagem e da

fala, tem sido recorrente no percurso da dupla de artistas. Junto à ideia de colaboração no

processo criativo, talvez seja aquilo que

mais caracteriza o seu trabalho — mesmo quando as imagens o povoavam com mais veemência,

principalmente através da escultura, mas também do vídeo, eram as palavras a aparente

preocupação primária e, especificamente, o que acontecia

quando elas encontravam umas às outras.

Como é sugerido no texto Silogismos em

Movimento, escrito por Sofia Lemos e publicado a propósito do catálogo Visões

do Mal-entendido, sobre o trabalho da dupla,

parte daquilo que é objeto de estudo do campo da linguística (a origem da linguagem) pode

facilmente ser mal-interpretada e subjugada quando analisada sob uma perspectiva que

privilegie demasiadamente uma visão de mundo pautada

pelo racionalismo europeu. Contra tal subjugação, podemos pensar que a valorização, ainda

que antes no campo artístico do que na teoria linguística, do sensível na concepção da

linguagem possa emergir como uma possibilidade.

O que, talvez, significaria compreender a linguagem a partir das relações capazes de gerar

subjetividades, sejam elas entre uma pessoa e outra ou entre o humano e o não-humano. Tal

ideia irrompe com uma força sutil no trabalho

da Musa, mesmo quando ainda em um estágio embrionário, e permeia a sua produção de maneira

constante.

Vistas da intervenção "Solar Boat" na BoCA Bienal, 2021.

II

Ao olhar para os últimos treze anos de trabalho

desenvolvido pela dupla de artistas e por seus colaboradores, tal interação entre

sensibilidades parecia quase sempre exigir ser manifestada em forma de imagens. Nos

projetos anteriores e até a exposição The I of the Beeholder (2020), na Fundação

Carmona e Costa, havia uma predominância da escultura aliada ao som e o vídeo como veículos

para essa prolongada conversa. Entretanto,

em certa altura, tais componentes plásticas pareceram mais tímidas, por vezes quase

ausentes. Essa impressão era capaz de sugerir uma mudança na atitude artística da dupla, ou

então uma espécie de fechamento de ciclo — como

se as suas ideias nascessem a demandar serem plasticamente materializadas e, ao longo do

tempo, fossem se abstraindo até que sobrasse de si apenas uma memória sonora. Ao menos era

esse o engano, até ouvir Miguel e Eduardo a

planejarem um futuro para o seu trabalho, no qual as imagens voltam a reivindicar um papel

fundamental.

Do privilégio de poder, pela primeira vez, trabalhar ao seu próprio

ritmo e sem a obrigação de cumprir com datas

para um projeto específico, os dois artistas dividem comigo aquilo que está a se formar em

seus horizontes e que tem feito parte de suas rotinas de trabalho ao longo dos últimos dois

anos. À procura de pessoas cuja prática

diária envolva o conhecimento de algum ofício — e, por tal, se entendem as atividades que

exigem uma especialização e que, de alguma forma, envolvam um sentido de mecanização do

corpo —, a dupla inaugurou uma investigação imagética

por aquilo que acontece quando a tecnologia é percebida como uma extensão do humano, como se

referem ao discorrerem sobre o assunto. Por uma metodologia quase literal, tal investigação

envolve imagens cuja captura depende de

dispositivos de filmagem que simulam esse prolongamento do corpo humano. Em certa medida, a

própria escolha por tais meios de captura de imagem se relaciona com a conotação mecanicista

do termo “ofício”. Para além disso, as

pessoas envolvidas nessa nova jornada da dupla têm trabalhos que necessariamente envolvem o

cuidado ou a proximidade com outres (sendo esses humanos ou não-humanos).

Ouvi-los em

suas especulações ainda dispersas sobre

o futuro dessa pesquisa proporcionou o vislumbre de dois pontos que são passíveis de serem

identificados enquanto centrais em sua prática artística: a ideia de um novo trabalho ser,

na verdade, uma espécie de vida dupla daquilo

que foi realizado anteriormente — como se a obra fosse sempre uma obra em aberto, seguindo

uma definição feita por Luigi Ghirri —; e a importância da ambiguidade para uma prática que

é sempre limítrofe: que anuvia as fronteiras

de autoria, renega a necessidade institucional de categorização dentro da arte contemporânea

e afirma a vontade de existir e se bastar em si mesma.

Sobre a obra aberta, é sempre

instigante testemunhar um trabalho que

encontra em si mesmo a razão para as suas metamorfoses. Que permanece flexível e passível de

mudanças, e avança trazendo em si resquícios do que fora anteriormente. Que existe à mercê

dos caminhos que o atravessam. E, sobre

a ambiguidade, há certa graça em se ver diante daquilo que não se permite definir ou revelar

por inteiro. Do que constantemente serpenteia entre as categorias criadas pela necessidade

humana de catalogação. Do que é fugidio.

Contínua e indisciplinada, assim se pode caracterizar a prática da Musa Paradisiaca.

Exhibition view "Solar" at Appleton Square, Lisbon, 2023.

English Version

From an artificial Sun, a source of concentrated light and heat, time inside the dark room

is marked by a cyclic extinguishing and rekindling — a simulation of the intermittent nature

of the course of a day. All materiality around

dissipates, leaving the body in a black void, making this sun the only possible spatial

reference. It's as if we are witnessing a moment beyond the future, in which few remnants of

humanity persist. Only here, the Sun transmuted

into an oppressive metallic structure, dividing the origin of its light, once singular, into

small spheres, like replicas of itself. On the opposite end of the room where this new Sun

ostentatiously makes its presence felt,

three objects designed for listening and sound reproduction disturb the sepulchral silence.

For the first time since we entered the space, some familiar presence is recognizable: an

adult and a child engage in a conversation

without perceptible linearity or coherence, but with an evident dialogic character. Immersed

in the somber emptiness of this spectacularly constructed space, we lose the ability to

distinguish the beginning from the end, the

emergence from the disappearance of language, the past from the present, and the present

from the future.

The ambiguity of this state is not accidental but a characteristic

developed throughout a journey and central

to the creative impulse of the duo who have been producing works under the banner of Musa

paradisiaca since 2010. In Solar, an exhibition inaugurated last May at Appleton [Box], this

ambiguity is taken to a certain extreme.

Perhaps this is a consequence of processes that often involve the active participation of

many people collaborating with the duo composed of Eduardo Guerra and Miguel Ferrão.

Specifically in this exhibition, curator Claudia

Pestana played a fundamental role in the creative puzzle responsible for the reappropriation

of Solar Boat — an experience bordering on performance and happening that took place during

the BoCA biennial in 2021, where the same

sound installation was presented on a solar-powered boat trip across a lagoon in Ria

Formosa, Faro, Algarve.

In the journey from the vast and idyllic Algarve landscape to

the white cube of the gallery, the representation

of solar presence — as well as the understanding of the word itself — transformed from

abstraction to materiality, while spatiality went in the opposite direction, completely

detached from any figurative or material reference

and finding a new way to exist in the black void. In Solar, the only images that are

revealed are those that thought, in conversation with the sound installation, forges in the

imagination, whether they are anchored in a dialogic

perception of the work or not. This interaction that is created configures a hypothesis,

intrinsically related to the practice of Musa paradisiaca: that of a protolanguage born in

the interstices of the senses, words, images,

and everything that shapes the sensory.

This exercise, which could be referenced as a

kind of abstraction, reevaluation, or even disarticulation of language and speech, has been

a recurring theme in the duo's work. Alongside

the idea of collaboration in the creative process, this is perhaps what characterizes their

work the most — even when images populated it more vigorously, mainly through sculpture but

also through video, words seemed to be

the primary concern, specifically what happened when they encountered each other.

As

suggested in the text Silogisms in Motion, written by Sofia Lemos and published in the

context of the Visions of Misunderstanding catalog

about the duo's work, part of what is the subject of study in the field of linguistics (the

origin of language) can easily be misinterpreted and subjugated when analyzed from a

perspective that excessively privileges a worldview

based on European rationalism. Against such subjugation, we can think that the valuation,

even if firstly in the artistic field than in linguistic theory, of the sensory in the

conception of language may emerge as a possibility.

This perhaps means understanding language from the relationships capable of generating

subjectivities, whether they are between one person and another or between the human and the

non-human. Such an idea emerges with subtle

force in Musa's work, even when still in an embryonic stage, and permeates their production

consistently.

Exhibition view "The I of the Beeholder" at Fundação Carmona e Costa, Lisbon, 2020.