05

Interview with Ângela Ferreira

(Interview)

(4 photos / 7187 words)

(Comissioned by Contemporânea)

(2023)

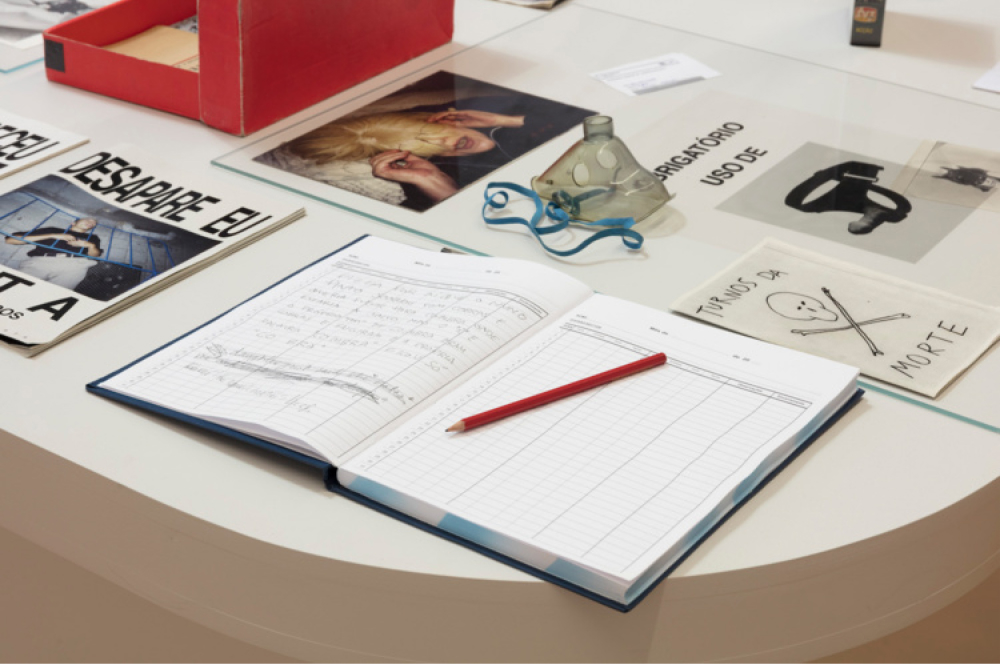

Vistas gerais da exposição na Kunsthalle Recklinghausen.

Portuguese Version

Nos Coruchéus, há um ateliê que tem a porta sempre aberta — como me diz Ângela

Ferreira, quando a contacto para propor uma entrevista. É nesse espaço, entre maquetes,

registros fotográficos e catálogos de exposições passadas,

que as obras que compõem a carreira da artista coexistem e a fazem pensar o futuro. Em horas

que mais pareceram alguns minutos, falamos sobre a escolha das obras que compõem a sua

primeira exposição antológica na Alemanha —

patente até o dia 6 de Agosto na Kunsthalle Recklinghausen —, sobre as maneiras que a sua

própria história moldou a sua prática artística e sobre outras questões que fazem dela uma

artista de relevância para o contexto da arte

contemporânea em Portugal.

Paula Ferreira (P.F.)Como surgiu o convite

para esta exposição antológica na Kunsthalle Recklinghausen, quer falar sobre

isso?

Ângela Ferreira (A.F.)Devo muito

essa exposição ao contributo do curador Nico Anklam. O convite para ela, esta que é a minha

primeira individual na Alemanha, surgiu a partir da vontade dele em fazer uma exposição que,

de alguma maneira, mostrasse a história

do meu trabalho. Que abordasse os trabalhos mais relevantes dentro da minha prática

política, sem necessariamente serem aqueles que marcaram mais a minha vida, e que explorasse

abordagens diferentes sobre o meu corpo de trabalho.

Além disso, Recklinghausen faz parte da antiga zona mineira da Alemanha, portanto há lá um

histórico muito ligado ao assunto. Ao conhecer os trabalhos que fiz sobre a questão das

minas em França, na Alemanha, em Lubumbashi,

Anklam quis que isso estivesse presente de alguma forma. Portanto, a nossa lógica de

pensamento foi começar por Entrer Dans La Mine — por ventura, não é a obra mais marcante da

minha vida, mas é uma obra que me interessa. Em

primeiro lugar, porque é uma escultura que utiliza o edifício como um plinto, é uma espécie

de obra pública, que não está no passeio, pertence ao edifício do museu mas não está dentro

dele, está em cima, e isso para mim era

interessante. E, depois, ela não funciona sozinha, precisa de uma performance que traz dois

cantores congoleses a cantar uma música — dessa vez, interpretada por Shak Shakito e

Claudine Mpolo. A escultura ainda se desdobra

como uma homenagem ao Dan Flavin. Por causa das luzes, ela de dia é uma coisa e, à noite, é

outra.

P.F.E Entrer Dans La Mine também partilha uma

característica muito presente no seu corpo de trabalho,

que é a direta referência a movimentos de levante social ou com forte senso de coletividade,

tal qual em For Mozambique, também presente na exposição. Entretanto, o espaço da

arte contemporânea é o institucional, o

museu, a galeria. Existem algumas fugas possíveis a esse espaço como mencionou, mas são

pontuais. Na maioria das vezes, sente que é um desafio conciliar esse discurso político que

desperta para o coletivismo à produção para

espaços institucionais?

A.F.Sinto que é um desafio imenso… Durante os

primeiros anos da minha prática artística, tive muito pudor em ser artista por causa do

contexto político — estávamos na África do Sul,

durante o Apartheid. E eu tive muitas dúvidas sobre como conciliar o meu gosto por

fazer arte contemporânea, aquela que pensa e que nos ajuda a pensar, e, ao mesmo tempo,

poder representar os grupos com quem estava

a trabalhar. Quando saí das Belas-Artes, estava a trabalhar com um grupo de mulheres que

pintava murais, que fazia cerâmicas, trabalhávamos para o Community Art Project,

fazíamos t-shirts para reuniões políticas, panfletos

e, portanto, era uma atividade visual muito integrada num grupo. Esse era o grande dilema do

início da minha prática. E então, há um momento em que decido que consigo fazer arte

contemporânea desde que o assunto do meu trabalho

seja sobre a comunidade. Mesmo que o trabalho acabe sendo bastante conceptual e até

esotérico — se assim o quiseres chamar —, há um ponto de entrada nele que é pela comunidade,

é acessível a ela e é completamente compreensível

por ela.

P.F.Daí as referências…

A.F.Sim, como o Bob

Dylan, que é uma porta de entrada global. Mas também, por exemplo, Sites and

Services, um dos primeiros trabalhos que fiz,

tem fotografias tiradas em Khayelitsha, nos subúrbios de Cape Town, que estava a ser

construída no início dos anos 90 e era um assunto de grande discussão política dentro do

país e da cidade. Era à beira da autoestrada que

vai do centro ao aeroporto. Portanto, não havia ninguém que olhasse para as fotografias e

não soubesse que aquilo era Sites and Services, em Khayelitsha, Cape Town. Depois,

o que eu faço com as esculturas, que é um

ramificar, ir a um lado mais minimalista, pode não ser totalmente acessível, mas passa a ser

porque o espectador entra primeiro pelas fotografias, por aquilo que conhece e, então, vai

ter de perguntar a si próprio o que é isto

e qual a relação entre as esculturas e as fotografias. Por outro lado, o espectador que vem

de fora e não percebe nada de Khayelitsha, mas percebe de minimalismo, conhece o Donald

Judd, o Flavin, entra pelas esculturas, reconhece

os códigos formais do minimalismo, e vai se perguntar sobre a relação delas com as

fotografias… Quando comecei esse trabalho, nos anos 90, as pessoas me perguntavam qual era o

significado das coisas, e hoje, com o recuo de

trinta anos, consigo perceber, mas na altura eu só sabia dizer que o significado estava

algures entre uma coisa e outra. O que é estranho é que a minha resposta não estava

errada.

O meu problema era como comunicar com

a minha comunidade e como fazer arte dentro do discurso da arte contemporânea, que fosse

válida e ao mesmo tempo acessível. Eu não queria ser uma artista que faz artesanato, mas

também não sou americana e nem europeia nem vivo

dentro daquela reiteração do modernismo europeu. Não me identificava com aqueles homens,

americanos, europeus, minimalistas… Não acreditava na crença deles de que o objeto acaba em

si próprio, que tem o fim em si próprio. Quer

dizer, como poderia eu estar em África a afirmar que os objetos acabam em si próprios? Nessa

altura, comecei a perceber um certo “fascismo” do modernismo europeu, que impunha que aquilo

é que era a linguagem da arte contemporânea.

Eu gosto da linguagem, mas não acredito que isto acabe aí. E, assim, começo a gerir as

comunidades e as pessoas com quem convivo dentro do meu trabalho.

Essa preocupação em

trazer os grupos com quem trabalhei está sempre

no meu espírito de alguma maneira… E uma coisa que não costumo falar, mas que interessa ao

assunto do coletivo, da comunidade: uma das crenças que tínhamos na altura era que não

fazíamos distinções hierárquicas entre aquilo

que era high art e low art, não víamos uma pintora ou uma escultora como

mais credível do que uma ceramista, uma designer ou uma pessoa que fazia roupa. Estávamo-nos

a ensaiar politicamente dentro de uma ideologia

de democracia, de igualdade e de inclusão, portanto era contranatura pensar que ser

artista enquanto escultora era mais importante do que ser designer a fazer panfletos

políticos, ou trabalhar para os sindicatos das

minas a fazer publicações, para nós havia uma espécie de plafond de igualdade entre

as práticas criativas. Chamávamos-nos cultural workers, não éramos pintoras,

escultoras, etc. Era a terminologia política

para afirmar que não pertencíamos à lógica do Apartheid, que tínhamos uma visão muito mais

inclusiva e democrática daquilo que são as práticas culturais.

P.F.É

interessante, porque dá para ver que vem da

sua própria história esta visão. A arte contemporânea, principalmente europeia, tem muito

culto ao indivíduo, ao artista relacionado à genialidade…

A.F.Sim, e

também tem muito que ver com o contexto da tradição

africana, com a ideia do artista, ou da pessoa que faz os artefactos dentro de uma

comunidade: não há esse culto ao génio, está mais integrado à comunidade. As pessoas têm os

seus papéis dentro da estrutura social coletiva

e o artista não é cultuado com essa ideia de genialidade e até esoterismo que há em um

contexto europeu. É claro que estávamos a negociar o fato de sermos africanos e estarmos em

África e termos de resolver o jeito que iríamos

ser dentro daquela sociedade, sendo que Cape Town também não é uma cidade africana

tradicional…

P.F.E vem também desse seu aprendizado dizer que não há

hierarquias entre as media que você utiliza? Entre

a fotografia e a escultura, por exemplo, e a primeira poder ser, na verdade, uma extensão da

segunda? Quero dizer, isso interessa porque as categorias dentro da arte contemporânea já

não são mais tão rígidas quanto um dia foram,

mas quando você começou elas ainda o eram, especialmente no contexto europeu. A própria

fotografia atingiu o patamar de arte há relativamente pouco tempo…

Vistas gerais da exposição na Kunsthalle Recklinghausen.

A.F.Vem completamente desse aprendizagem. Na altura, eu convivia com muitos

fotógrafos que tiveram um papel político importante na África do Sul, eram as pessoas que

estavam a fotografar o mal que o sistema do Apartheid estava a fazer e que mandavam

para fora para o resto do mundo ver. Portanto, eram pessoas esteticamente muito sofisticadas

e que, ao mesmo tempo, tiveram um papel importantíssimo dentro da luta contra o

Apartheid.

Inclusive, um dos pintores dos murais[1] era, na verdade, fotógrafo, então para

nós essa hierarquia não existia. Quando eu comecei a perceber que, no circuito ocidental,

nos anos 90, a fotografia é integrada, é trazida

para o discurso da arte contemporânea, lembro-me de pensar: isto não é nenhuma novidade para

mim. Ainda bem que toda gente agora concorda, mas nunca me tinha ocorrido que não fosse

assim… Por isso, o que tu dizes é verdade,

porque as nossas interações na África do Sul durante os anos noventa foram extremamente

educativas, marcantes e bem orientadas. Embora, na altura, não soubéssemos ainda disso, em

retrospectiva se percebe que já estávamos a

pensar esses problemas da arte contemporânea.

P.F.Quando fala sobre essa

visão que contrariava os discursos ocidentais da arte contemporânea, introduz uma questão

pertinente. O seu trabalho lida com problemas

bastante delicados, como o colonialismo e as suas consequências, mas, apesar disso, é muito

bem aceito dentro de Portugal e de outros países europeus. Arrisco dizer que isso se deve,

em partes, por você sempre ter trabalhado

dentro dos códigos formais da arte contemporânea europeia, acha que faz sentido colocar isso

nesses termos?

A.F.Como disse, a minha intenção sempre foi que se

pudesse entrar por aqui ou entrar por ali. Eu

não sou o público, não posso falar como uma pessoa inocente porque não o sou, mas penso que

isso seja muito possível, sim. Mas há duas coisas que talvez seja preciso nós, em 2023,

também falarmos: uma das razões que me trouxe

para Portugal, por exemplo, tem que ver com a minha própria tentativa de entender a relação

mal resolvida entre África e Europa. Muito cedo percebi que, apesar de o colonialismo ter

acabado oficialmente, essa relação está mal

resolvida. Sempre pensei que procurar entender onde as coisas tinham corrido mal ou como

ainda correm mal poderia ser um assunto no meu trabalho, portanto isso está muitas vezes

presente. Por outro lado, apesar de achar que

meu trabalho formalmente é fácil para um público europeu, também acho que, de dez ou quinze

anos para cá, houve uma disseminação de artistas africanos para cá e, com isso, a vinda

também de outras linguagens diferentes que

permitiram uma abertura muito grande do público europeu e ocidental. A ideia de que “isto é

que a linguagem aceitável para seres artista, inteligente, de primeira linha” já não é

definida de forma tão autocrática, nem do ponto

de vista museológico, nem do ponto de vista comercial, e, portanto, acho que esses tabus, de

certa maneira, felizmente estão a desconstruir-se. Não sei se isso facilita a recepção do

meu trabalho ou não, mas estou muito consciente

de que estamos muito mais disponíveis para outras linguagens.

P.F.E

então, sendo essa a sua primeira exposição antológica na Alemanha, como percebeu a relação

entre o público e a sua obra? Há diferenças

substanciais entre a maneira que o público alemão a recebe e o

português?

A.F.Muito. É estranho, mas há. E não experimentei isso só na

Alemanha, mas também em França. Em Portugal, há dificuldades emocionais

— não sei se todos os países têm esse problema, mas Portugal tem. Há certos assuntos em que

tocas e não vais para frente… Eu acho que ainda não nos focamos em tentar digerir certas

coisas por aqui. O que eu noto no meu trabalho

é que, às vezes, quando abordo certos assuntos, por exemplo em A Tendency to

Forget, há uma reação fortíssima. As pessoas sentiram-se ofendidas por eu ousar

apontar alguns problemas metodológicos na abordagem colonial

dos etnógrafos Jorge e Margot Dias. Quando exponho na Alemanha, não tenho esse problema

porque há a distância. Os alemães têm a sua própria História e eles entendem o sentido de

trauma, de culpa e de carregar o peso da História

de maneira muito real — o que faz com que haja uma empatia, distanciada, mas real.

Entrer Dans La Mine, por exemplo, foi muito mais fácil para o público, pois há uma

proximidade com as histórias das minas. Há lá muitas

pessoas cujos tios, avós e outros familiares eram mineiros, portanto quando eles veem esse

trabalho, há uma empatia mais direta — inclusive, há um coro dos mineiros da cidade que vai

cantar a propósito da exposição.

Da

mesma forma, ao apresentar Talk Tower For Ingrid Jonker, houve uma empatia imediata

por causa da história dessa poetisa — cujo pai era o chefe da censura política na África do

Sul do Apartheid. Na frase: “quando

ela conseguiu perceber que não poderia haver futuro para ela em seu país, suicidou-se”,

consegui perceber na audiência essa reação imediata.

Mas isso é agora. No início,

quando comecei a trabalhar, havia pouca gente

que entendia o meu trabalho, os anos 90 foram muito sozinhos. As pessoas aqui não tinham

lido nada pós-colonial, não tinham ferramentas teóricas, estavam muito orientados para uma

visão europeia. E eu já trazia as ferramentas

conceptuais, do orientalismo ao pós-colonialismo. Havia, na altura, dois ou três curadores —

e aí acho que tens razão em dizer que o fato da linguagem formal do meu trabalho ser mais

familiar a eles ajudou bastante. Lembro-me

que quando mostrei Sites and Services pela primeira vez em Lisboa, em 92, alguém escreveu:

“é pena que uma escultora tão capaz estrague o seu projeto com as fotografias que mostra

junto”. Esperavam uma coisa muito formalista,

mas eu não levo a mal. Em 98, fiz uma performance, Untitled 1998, e depois escrevi

um texto chamado Dar a Mão à Palmatória, em que escrevi — “não acredito na arte

formalista. Arte só por si, para ser bela,

para mim, não tem valor nenhum. Acredito que tem de se pôr conceitos e ideias dentro da

arte. Mas, para não me chatearem mais, fiz uma obra que não tem título. Aqui têm, entendam

se quiserem.”—. Era eu a fazer ginástica no

Estádio Nacional, que é um estádio da altura do fascismo. Esses foram os anos 90:

interessantes, mas bastante solitários…

P.F.Rádio Voz da

Liberdade, que integra a exposição, ajuda a desconstruir

uma mitologia portuguesa sobre os movimentos responsáveis pela dissolução do Estado Novo e,

por consequência, pelo 25 de Abril, ao apontar para uma contribuição fundamental vinda de

uma estação de rádio da Argélia. Essa espécie

de revisão da História é algo que pretende prosseguir nos próximos

trabalhos?

A.F.Esse trabalho está muito relacionado àquilo que me

interessa nesse momento, que é procurar modelos ou histórias de coisas

que contradigam essa visão de que Portugal resolveu tudo sozinho, ou de que a Europa é que

mostra à África como há de resolver os problemas, é que dá os protótipos do desenvolvimento…

interessa-me olhar para os problemas entre

a Europa e a África não apenas em trabalhos de denúncia, como em A Tendency to Forget,

Amnésia, etc. Agora, quero procurar casos em que a África seja um exemplo de

libertação, de ensinamento. Rádio Voz da Liberdade vem daí… Esse é o género de

história que me interessa no momento.

P.F.Ou seja, a realidade a

contradizer as narrativas hegemônicas…

A.F.Sim, e também procurar a

complexidade das situações,

porque nada é completamente linear. As narrativas grandes estão na mesa, toda gente as tem.

A mim interessa uma coisa um pouco diferente.

P.F.Quando falamos em

narrativas hegemônicas, há outra questão que

é o ato de arquivar enquanto instrumento de poder — ação que foi e vem sendo praticada pelos

países europeus e que beneficia até hoje muitos museus e coleções que possuem um espólio

imenso oriundo do colonialismo. Precisamos

pensar que, em muitos casos, a Europa resguardar para si o direito de arquivar a História

dos Outros implica que esses Outros não tenham direitos sobre a sua própria História. O seu

trabalho, muitas vezes, coloca isso em causa.

Qual o papel que você acredita que cabe aos artistas nesse debate?

A.F.É

uma questão delicada, mas não mais do que devolver espólios artísticos, por exemplo. Acho

que estamos no início do mundo da restituição,

essa discussão está na mesa — não sei até que ponto está a acontecer realmente, já houve

algumas devoluções, alguns países já debatem o assunto melhor do que outros, mas o debate

existe e não acho que vá voltar atrás. O caso

do arquivo é mais complexo, porque é mais ilusivo. Um objeto existe, tem peso, está num

museu, é material, já um arquivo pode ser uma coisa escondida, menos ou mais acessível, a

depender… Mas para mim, não há o que discutir.

As coisas que não pertencem a um lugar não deveriam lá estar. Não sou muito tolerante nessa

questão, as coisas devem ser devolvidas. O arquivar como forma de poder decorreu de os

países europeus, para além de estarem a dominar

outros países e, portanto, terem capacidade de extração de materiais, também tinham os

recursos financeiros para arquivar e mantê-los. Quem é dono dos arquivos, é dono da

História.

Mas há dois assuntos aqui: uma coisa

é onde os arquivos estão e outra coisa é a acessibilidade deles. Eu também acho que, se os

arquivos forem devolvidos aos lugares que eles pertencem e não estiverem acessíveis às

pessoas, torna a situação bastante complicada.

É preciso lembrar do que diz Achille Mbembe: se não mexes nos arquivos, eles estão mortos, é

como se estivessem enterrados numa sepultura e a História não se move, está fixa. Se ninguém

for lá para mexer nos arquivos, vasculhá-los

e ressignificá-los, eles ficam moribundos, a História não se altera, não há crítica. E, por

isso, acho que o arquivo não só deve pertencer ao lugar onde pertence, mas tem de estar

acessível, porque um arquivo não acessível

é pior ainda do que um arquivo no lugar errado.

P.F.Ao rememorar a sua

trajetória, a propósito dessa exposição antológica, houve oportunidade para mudar ou

reconstruir relações com o seu próprio trabalho?

A.F.Sim,

claro. Por exemplo, nessa exposição, Rádio Voz da Liberdade foi dividido em dois

andares. Originalmente, uma das esculturas tem seis metros de altura, o que é mais que o pé

direito do espaço da Kunsthalle, mas o curador

insistiu em mostrá-la. Então dividimos: essa escultura aparece no último andar sem a torre

que originalmente a sustenta, e a parte de baixo da estrutura aparece no andar inferior.

Portanto, quando perguntaste, antes de começarmos

a entrevista, se a escolha das obras tinha que ver com o espaço, a resposta era sim e não…

Eu sou flexível sobre mudar os formatos dos trabalhos enquanto eles ainda são meus, a

deixá-los abertos para mudarem ou serem apresentados

de novas maneiras. Nessas exposições, tens o privilégio de recriar as relações entre os

trabalhos. Outro exemplo é a escultura de Realistic Manifesto, que me fez pensar numa

proximidade sua com Double Sided, trabalhos feitos

em alturas diferentes da minha vida — sendo o primeiro, ao mesmo tempo, o mais antigo e um

dos mais recentes trabalhos meus.

P.F.Parece que os trabalhos vão se

prolongando uns nos outros…

A.F.Sim.

E construímos a exposição a pensar que o andar mais alto seria o das torres de rádio, com

Rádio Voz da Liberdade, como se começássemos de forma mais aérea e fossemos

descendo à terra até chegar a Sites and Services.

No andar mediano, há a obra For Mozambique, que é uma obra sonora que preenche o

espaço com o seu som.

P.F.A ideia de utopia é muito presente no seu

trabalho. Acha que ela é necessária para seguir

fazendo arte contemporânea?

A.F.Para mim, é. É a ideia de estar a

trabalhar para qualquer coisa, para um fim. Não tens necessariamente de chegar a esse fim,

mas estás a trabalhar para isso, para algo além

de ti. Só fazer coisas belas é fácil. Eu gosto da ideia de que estou a caminhar em direcção

a algo que é melhor do que aquilo que temos. E é por isso também que dou aulas. Dei a vida

inteira e continuo a dar, tem a ver com

a partilha, com a comunicação com as pessoas, com investimento… São muitos anos a dar aulas

e, para mim, é muito importante essa ideia de construir um mundo melhor. Podes chamar

utopia. Talvez, por isso, muitas das minhas obras

tenham essa palavra no título…

[1] Aqui, Ângela se refere aos murais que pintava com o grupo Community Art Project e que, mais tarde, originou a obra Pan African Unity Mural, exposta em 2018 no MAAT.

Exhibition view at Kunsthalle Recklinghausen.

English Version

In the Coruchéus, there is a studio which the door is always open – as Ângela

Ferreira tells me when I contact her to propose an interview. It is in this space, amid

models, photographic records, and catalogs of past exhibitions,

that the works that make up the artist's career coexist and make her contemplate the past

and the future. In hours that felt more like minutes, we discussed the selection of works

for her first anthological exhibition in Germany

– current until August 6th at Kunsthalle Recklinghausen. We talked about the ways in which

her own history has shaped her artistic practice and other issues that make her an artist of

significance in the context of contemporary

art in Portugal.

Paula Ferreira (P.F.)How did the invitation for this

anthological exhibition at Kunsthalle Recklinghausen come about? Would you like to talk

about it?

Ângela Ferreira (A.F.)I

owe this exhibition a lot to the contribution of curator Nico Anklam. The invitation for my

first solo exhibition in Germany came from his desire to create an exhibition that, in some

way, would showcase the history of my work.

It should address the most relevant works within my political practice, without necessarily

being the ones that have marked my life the most, and explore different approaches to my

body of work. Moreover, Recklinghausen is

part of the former mining region of Germany, so there's a strong historical connection to

the subject. After getting to know the works I did about mining issues in France, South

Africa, and the Democratic Republic of Congo,

Anklam wanted that to be somehow present. Therefore, our line of thought was to start with

Entrer Dans La Mine — perhaps it's not the most significant work of my life, but it's a work

that interests me. Firstly, because it's

a sculpture that uses the building as a plinth, a kind of public work that's not on the

sidewalk, it belongs to the museum building but is not inside it, it's on the roof, and that

was interesting to me. Then, it doesn't function

alone; it requires a performance that brings two Congolese singers to perform a song — this

time performed by Shak Shakito and Claudine Mpolo. The sculpture also unfolds as a tribute

to Dan Flavin. Due to the lights, it's one

thing during the day and another at night.

P.F.Entrer Dans La Mine also

shares a characteristic that is very present in your body of work, which is the direct

reference to social uprisings or strong senses

of collectivity, as seen in For Mozambique, also in the exhibition. However, the space of

contemporary art is institutional, in the museum, the gallery. There are some possible

escapes from this space, as you mentioned, but

they are sporadic. Most of the time, do you feel it's a challenge to reconcile this

political discourse that awakens collectivism with production for institutional

spaces?

A.F.I feel it's an immense challenge...

During the early years of my artistic practice, I had a lot of reluctance to be an artist

because of the political context — we were in South Africa during apartheid. I had many

doubts about how to reconcile my taste for making

contemporary art, the kind that thinks and helps us think, while also being able to

represent the groups I was working with. When I left the Fine Arts, I was working with a

group of women who painted murals, made ceramics,

worked for the Community Art Project, made T-shirts for political meetings, pamphlets, and

thus, it was a highly visual activity integrated into a group. That was the main dilemma of

the beginning of my practice. And then there

was a moment when I decided that I could do contemporary art as long as the subject of my

work was about the community. Even if the work ends up being quite conceptual and even

esoteric, if you want to call it that, there is

an entry point for the community, it's accessible to them and completely understandable by

them.

P.F.Hence the references…

A.F.Yes, like Bob

Dylan, who is a global entry point. But also,

for example, Sites and Services, one of the first works I did, has photographs taken in

Khayelitsha, in the suburbs of Cape Town, which was under construction in the early '90s and

was a subject of great political discussion

within the country and the city. It was on the edge of the highway that goes from the city

center to the airport. So, there was no one who looked at the photographs and didn't know

that it was Sites and Services in Khayelitsha,

Cape Town. Then, what I do with the sculptures, which is branching out, moving towards a

more minimalist side, may not be entirely accessible, but it becomes so because the viewer

first enters through the photographs, through

what they know, and then they have to ask themselves what this is and what the relationship

is between the sculptures and the photographs. On the other hand, the viewer who comes from

the outside and doesn't understand anything

about Khayelitsha but understands minimalism recognizes Donald Judd, Flavin, enters through

the sculptures, recognizes the formal codes of minimalism, and wonders about their

relationship with the photographs... When I started

this work in the '90s, people asked me what the meaning of things was, and today, with a

thirty-year perspective, I can understand it, but at the time, all I knew was that the

meaning was somewhere between one thing and another.

What's strange is that my answer wasn't wrong.

My problem was how to communicate with

my community and how to make art, within the discourse of contemporary art, that was valid

and accessible at the same time. I didn't

want to be a craft artist, but I'm not American, European, or living within that reiteration

of European modernism. I didn't identify with those men, Americans, Europeans,

minimalists... I didn't believe in their belief that

the object ends in itself, that it has its end in itself. I mean, how could I be in Africa

stating that objects end in themselves? At that time, I began to understand a certain

dogmatism of European and Western modernism that

imposed that this was the language of contemporary art. I like the language, but I don't

believe it ends there. And so, I start to manage the communities and the people I live with

within my work.

This concern to bring

the groups I worked with is always in my mind in some way... And one thing I don't usually

talk about, but that is relevant to the subject of the collective, of the community: one of

the beliefs we had at the time was that

we didn't make hierarchical distinctions between what was high art and low art; we didn't

see a painter or a sculptor as more credible than a ceramicist, a designer, or someone who

made clothing. We were rehearsing ourselves

politically within an ideology of democracy, equality, and inclusion, so it was against

nature to think that being an artist as a sculptor was more important than being a designer

making political pamphlets, or working for

mining unions to make publications. For us, there was a kind of equality threshold among

creative practices. We called ourselves cultural workers; we weren't painters, sculptors,

etc. It was the political terminology to assert

that we didn't belong to the logic of apartheid, that we had a much more inclusive and

democratic view of cultural practices.

P.F.It’s interesting because one

can see that this perspective comes from your

own history. Contemporary art, especially European, often places a strong emphasis on the

individual and the artist associated with genius...

A.F.Yes, and it also

has a lot to do with the context of African

tradition, with the idea of the artist or the person who creates artifacts within a

community: there isn't that cult of genius, it's more integrated into the community. People

have their roles within the collective social structure,

and the artist is not venerated with the idea of genius and esotericism that exists in a

European context. Of course, we were negotiating the fact that we were Africans in Africa

and had to figure out how we would fit into

that society, especially considering that Cape Town is not a traditional African

city…

P.F.Does this also come from your realization that there are no

hierarchies between the mediums you use? Between photography

and sculpture, for example, with the former possibly being an extension of the latter? I

mean, this is interesting because the categories within contemporary art are no longer as

rigid as they once were, but when you started,

they still were, especially in the European context. Photography only recently achieved the

status of art…

Exhibition view at Kunsthalle Recklinghausen.